|

|

Saturday, November 14th, 2009

I'm glad I watched La Pointe-Courte when I did, as I'm now seeing loose parallels between it and everything I am reading... Sort of the archetypal melancholy romance.

Paco se habÃa sentado en cuclillas, algo más lejos y antes de abandonarme del todo, le pregunté:

--¿De qué vive la gente aqu�

Se entretenÃa en escurrir la arena entre sus dedos y no levantó, siquiera, la cabeza:

--De la pesca.

--¿Y tú? --Me extendà boca arriba y cerré los ojos--. ¿Qué quieres ser?

Su respuesta, esta vez, llegó en seguida:

--Mecánico.

Me dormÃ. TenÃa conciencia de que, al cabo de unas horas, olvidarÃa la fatiga del viaje y no deseaba otra cosa que cocerme lentamente, cara al sol.

En una o dos ocasiones, me desperté y vi que Dolores dormÃa también.

Con la vista perdida en el mar, Paco hacÃa escurrir aún la arena entre sus dedos.

Paco was squatting a bit further down the beach; before giving myself up to sleep, I asked him:

--What do people live on, here?

He was distractedly letting the sand run through his fingers; he didn't even raise his head:

--On fish.

--And you? --I turned my mouth up(?) and closed my eyes--. What do you want to be?

His response, this time, came directly:

--Mechanic.

I slept. I was aware that after a few hours, I'd forget the fatigue of the journey; I didn't want anything besides to let myself bake slowly, my face to the sun.

Once or twice, I woke up and saw that Dolores was sleeping too.

His gaze lost in the sea, Paco was still letting the sand run between his fingers.

I'm thinking I will work on a full translation of this story.

posted morning of November 14th, 2009: Respond

➳ More posts about Juan Goytisolo

|  |

Sunday, December 6th, 2009

Some nice imagery from the opening of Juan Goytisolo's story "Making the Rounds" from Para Vivir Aquà (I am really enjoying these stories about traveling in the south -- Goytisolo is from Barcelona and I think he was still living there when he wrote these stories): Some nice imagery from the opening of Juan Goytisolo's story "Making the Rounds" from Para Vivir Aquà (I am really enjoying these stories about traveling in the south -- Goytisolo is from Barcelona and I think he was still living there when he wrote these stories):

Viniendo por la nacional 332, más allá de la base hidronaval de Los Alcázares, se atraviesa una tierra llana, de arbolado escaso, jalonada, a trechos, por las siluetas aspadas de numerosos molinos de viento. Uno se cree arrebatado de los aguafuertes de una edición del Quixote o a una postal gris, y algo marchita, de Holanda. La brisa sople dÃa y noche en aquella zona y las velas de los molinos giran con un crujido sordo. Se dirÃa las helices de un ventilador, las alas de un gigantesco insecto. Cuando pasamos atardecÃa y el cielo estaba teñido de rojo.

Coming down N-332, past the hydro-naval base at Los Alcázares, you cross a flat landscape, with little forestation, marked at intervals by the cruciform outlines of windmills. One believes oneself transfixed in the etchings of an edition of the Quixote or in an old gray postcard from Holland, a bit faded. The breeze blows day and night in this region, and the windmills' sails turn with a muffled creaking. They bespeak the blades of a fan, the wings of a giant insect. When we passed through there it was getting late; the sky was stained with red.

This is kind of cool: Google Maps has streetview for Murcia. Here is a view along N-332 heading south, midway between Los Alcázares and Cartagena:

posted morning of December 6th, 2009: Respond

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

Sunday, January 31st, 2010

Aquella noche Jacinta vio a ZacarÃas de nuevo en sueños. El ángel ya no vestÃa en negro. Iba desnudo, y su piel estaba recubierta de escamas. Ya no le acompañaba su gato, sino una serpiente blanca enroscada en el torso. Su cabello habÃa crecido hasta la cintura y su sonrisa, la sonrisa de caramelo que habÃa besado en la catedral de Toledo, aparecÃa surcada de dientes triangulares y serrados como los que habÃa visto en algunos peces de alta mar agitando la cola en la lonja de pescadores. Años mas tarde, la muchacha describirÃa esta visión a un Julián Carax de dieciocho años, recordando que el dÃa en que Jacinta iba a dejar la pensión de la Ribera para mudarse al palacete Aldaya, supo que su amiga la Ramoneta habÃa sido asesinada a cuchilladas en el portal aquella misma noche y que su bebé habÃa muerto de frÃo en brazos del cadáver. Al saberse la noticia, los inquilinos de la pensión se enzarzaron en una pelea a gritos, puñadas y arañozos para disputarse las escasas pertenencias de la muerta. Lo único que dejaron fue el que habÃa sido su tesoro más preciado: un libro. Jacinta lo reconoció, porque muchas noches la Ramoneta le habÃa pedido si podÃa leerle una o dos páginas. Ella nunca habÃa aprendido a leer.

That night, Jacinta again saw ZacarÃas in her dreams. The angel was no longer clothed in black. He was nude, and his skin was covered with scales. And he was no longer accompanied by his cat; instead a white serpent twined around his torso. His hair had grown down to his waist, and his smile -- the caramel smile which she had kissed in the cathedral of Toledo -- appeared to be cut through by triangular teeth, serrated like those she had seen in some fish of the high seas, their tails writhing at the fish market. Years later, the girl would describe this vision to a Julián Carax eighteen years old, remembering that on the day when Jacinta was leaving the Ribera boarding house to move to Aldaya's mansion, she learned that her friend Ramoneta had been murdered, stabbed in the doorway that same night, and that her baby had died of exposure in the corpse's arms. On learning the news, the tenants of the boarding house got in a screaming fight, throwing fists and scratching in a row over the dead woman's meager possessions. The only thing left was what had been her most cherished treasure: a book. Jacinta recognized it, for on many nights Ramoneta had asked if she'd read a page or two. Herself, she had never learned to read.

A key bit of plot development occurred at the end of Chapter 28, which was that Daniel had his first sexual experience*, with Bea. This seems to have opened up the book a lot, for the time being at least (as of Chapter 31) -- Daniel seems like a much better narrator for his experience. Daniel and FermÃn's visit to the asylum has been gripping (though the detail about the old man's making Daniel promise to find him a hooker seemed a little silly.) The mysticism in Jacinta's story is seeming much more authentic to me than the mystical bits in the first half of the book.Maybe the most striking thing is, the construction of the book is getting less transparent -- in the first half of the book, it has often been too blindingly obvious, just where Ruiz Zafón is going with each detail of the plot. As Daniel and FermÃn move through Santa LucÃa and listen to Jacinta's story, it is refreshingly hard to see where they're going.

* Or, well, nix that -- I was reading too much into the ellipses. But they kissed passionately, which for the purposes of this story seems to come to about the same thing.

posted evening of January 31st, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about La sombra del viento

|  |

Sunday, February 7th, 2010

At 3% today, I read about the forthcoming Op Oloop, which will be the first of Juan Filloy's 27 novels to appear in English. Nice! It was also the first I had heard of Filloy, who appears to have had a long and important career. In honor of the occasion, I will try my hand at translating his short story "La vaca y el auto."

The cow and the car

by Juan Filloy

The rain has firmed up the unpaved road's surface. The recently rinsed atmosphere is fresh and clean. The sun's glory shines down at the end of March.

A car comes along at a high velocity. Beneath the pampa's skies -- diaphanous tourmaline cavern -- the swift car is a rampaging wildcat.

The moist fields give off a masculine odor, exciting to the lovely young woman who's driving. And accelerating, accelerating, until the current of air pierces her, sensuous. But...

All of a sudden, a cow. A cow, stock-still in the middle of the roadway. Screeching of brakes, shouting. The horn's stridency shatters the air. But the cow does not move. Hardly even a glance, watery and oblique, she chews her cud. And then, she bursts out:

-- But señorita!... Why all this noise? Why do you make such a hurry, when I'm not interested in your haste? My life has an idyllic rhythm, incorruptible. I am an old matron who never gives way to frivolity. Please: don't make that racket! Your clangor is scaring the countryside. You do not understand why; you don't even see it. The countryside flies past, by your side; your velocity turns it into a rough, variegated visual pulp. But I live in it. It is where I hone my senses, they are not blunt like yours... Where did you find this morbid thirst which absorbs distance? Why do you dose yourself with vertigo? You subjugate life with urgency, instead of appreciating its intensity. Come on! lay off the horn. Time and space will not let themselves be ruled by muscles of steel and brass. Speed is an illusion: it brings you sooner to the realization of your own impotence. The signifier of all culture is the intrinsic slowness of the unconscious, which unconsciously chooses its destiny. But you already know yours, girl: to crash into matter before you crash into materialism. So, good. Don't get mad! I'm moving. Let your nerves once again become one with the ignition. Reanimate, with explosions of gas, your motor and your brain. The roadway is clear. Adiós! Take care of yourself...

The car tears away, muttering insults in malevolence and naphtha.

Parsimonious, chewing and chewing, the cow casts a long, watery gaze. And then a lengthy, ironic moo, which accompanies the car towards the curve of the horizon...

And while I'm doing this: I get a lot of misdirected Google hits by people looking for "a translation of El dios de las moscas" or similar phrases -- I had never heard of this story until people started coming to my site looking for it; but I like it. (But do your own homework, people!) It is by Marco Denevi. Dare I say, a little bit in the manner of Borges.

The god of the fliesby Marco Denevi

The flies imagined their god. It was another fly. The god of the flies was a fly, sometimes green, sometimes black and golden, sometimes pink, sometimes white, sometimes purple, an unrealistic fly, a beautiful fly, a monstrous fly, a fearsome fly, a benevolent fly, a vengeful fly, a righteous fly, a young fly, an aged fly, but always a fly. Some of them augmented his size until he was enormous, like an ox, others pictured him so tiny he could not be seen. In some religions he had no wings («He flies, he sustains himself, but he has no need of wings»), in others he had an infinite number of wings. Here his antennæ were arranged like horns, there his eyes consumed all of his head. For some he buzzed constantly, for others he was mute, but it meant the same thing. And for everyone, when flies died, they would pass in rapid flight into paradise. Paradise was a piece of carrion, stinking, rotted, which the souls of dead flies would devour for all eternity and which was never consumed; for this celestial offal would continually be replenished and grow beneath the swarm of flies. --of the good ones. For also there were evil flies; for them there was a hell. The hell of the condemned flies was a place without shit, without waste, without garbage, without stink, with nothing at all, a place clean and sparkling and to top it off, illuminated by a dazzling light; that is to say, an abhorrent place.

posted evening of February 7th, 2010: 1 response

➳ More posts about Writing Projects

|  |

Thursday, March 25th, 2010

There is a tricky bit of translation at the beginning of Woyzeck:

HAUPTMANN: Langsam, Woyzeck, langsam; eins nach dem andern! Er macht

mir ganz schwindlig. Was soll ich dann mit den 10 Minuten anfangen,

die Er heut zu früh fertig wird? Woyzeck, bedenk Er, Er hat noch seine

schönen dreißig Jahr zu leben, dreißig Jahr! Macht dreihundertsechzig

Monate! und Tage! Stunden! Minuten! Was will Er denn mit der

ungeheuren Zeit all anfangen? Teil Er sich ein, Woyzeck!

WOYZECK: Jawohl, Herr Hauptmann.

H: Es wird mir ganz angst um die Welt, wenn ich an die

Ewigkeit denke. Beschäftigung, Woyzeck, Beschäftigung! Ewig: das ist

ewig, das ist ewig - das siehst du ein; nur ist es aber wieder nicht

ewig, und das ist ein Augenblick, ja ein Augenblick - Woyzeck, es

schaudert mich, wenn ich denke, daß sich die Welt in einem Tag

herumdreht. Was 'n Zeitverschwendung! Wo soll das hinaus? Woyzeck, ich

kann kein Mühlrad mehr sehen, oder ich werd melancholisch.

W: Jawohl, Herr Hauptmann.

H: Woyzeck, Er sieht immer so verhetzt aus! Ein guter Mensch

tut das nicht, ein guter Mensch, der sein gutes Gewissen hat. - Red er

doch was Woyzeck! Was ist heut für Wetter?

W: Schlimm, Herr Hauptmann, schlimm: Wind!

H: Ich spür's schon. 's ist so was Geschwindes draußen: so ein

Wind macht mir den Effekt wie eine Maus. - [Pfiffig:] Ich glaub', wir

haben so was aus Süd-Nord?

W: Jawohl, Herr Hauptmann.

H: Ha, ha ha! Süd-Nord! Ha, ha, ha! Oh, Er ist dumm, ganz

abscheulich dumm! - [Gerührt:] Woyzeck, Er ist ein guter Mensch

--aber-- [Mit Würde:] Woyzeck, Er hat keine Moral! Moral, das ist,

wenn man moralisch ist, versteht Er. Es ist ein gutes Wort. Er hat ein

Kind ohne den Segen der Kirche, wie unser hocherwürdiger Herr

Garnisionsprediger sagt - ohne den Segen der Kirche, es ist ist nicht

von mir.

W: Herr Hauptmann, der liebe Gott wird den armen Wurm nicht drum

ansehen, ob das Amen drüber gesagt ist, eh er gemacht wurde. Der Herr

sprach: Lasset die Kleinen zu mir kommen.

H: Was sagt Er da? Was ist das für eine kuriose Antwort? Er

macht mich ganz konfus mit seiner Antwort. Wenn ich sag': Er, so mein'

ich Ihn, Ihn -

|

CAPTAIN: Slowly, Woyzeck, slowly; one thing at a time! You make me dizzy. What am I going to do with the 10 minutes that you'll save by the time you're done? Woyzeck, think of it, you've been alive a good thirty years already, thirty years! That's three hundred sixty Months! and Days! Hours! Minutes! What are you going to do with all that monstrous time? Pace yourself, Woyzeck!

WOYZECK: Yes sir, Captain sir. C: I get scared for the world when I think about eternity. Pay attention, Woyzeck! Forever: that's forever, that's forever -- you understand; but it's also not forever at all, it's just the blink of an eye -- Woyzeck, it frightens me, when I think of how the world goes around in a day. What a waste of time! What's going to come of that? Woyzeck, I can't even look at a mill-wheel any longer, without becoming melancholy. W: Yes indeed, Captain. C: Woyzeck, you always have such a hunted look! A good man wouldn't look that way, a good man with a clean conscience. -- But speak up, Woyzeck! How is the weather today? W: Bad, sir, bad: wind! C: I can feel it already. There's something blowing out there, such a wind sounds like a mouse to me. -- [whistles] I believe it's a South-North wind we have? W: Yes sir, Captain sir. C: Ha, ha, ha! South-North! Ha, ha, ha! Oh, you're a dummy, such a shameful dummy! - [turns] Woyzeck, you're a good man -- but -- [grandiose] Woyzeck, you have no morality! Morality, I mean like when somebody is moral, you understand. It's a good word. You have a child without the blessing of the Church, as our estimable chaplain says -- without the blessing of the Church, it's not just me saying that.

W: Captain sir, blessed God won't hold it against the little thing, whether somebody said Amen over it before it was made... The good lord said: Let the little children come unto me.

C: What are you saying there? What kind of a weird answer is that? You're confusing me with your answers. When I say "You", I'm talking about you, you... |

(From the script of Büchner's play, but the screenplay for Herzog's film seems to adhere pretty closely, at least in this portion of the film.) Two things: I did not know that capitalized Er could be used for formal address in the way that Sie is -- I reckon that must be an archaic or regional usage or Frau Rose would have told us in German class. (grin) It makes sense... The Captain's final line sounds much better in German than in (my) English, I think. And also, I can't communicate (or really, quite understand) the captain's slip into informal "du" in the middle of his second speech.The captain's soliloquies here are very clearly staged -- Dan Schneider presents that as a shortcoming of the movie; but it seems pretty charming to me.

posted evening of March 25th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Woyzeck

|  |

Saturday, March 27th, 2010

Creo que mi amistad con Borges procede de una primera conversación, ocurrida en 1931 o 32, en el trayecto entre San Isidro y Buenos Aires. Borges era entonces uno de nuestros jóvenes escritores de mayor renombre y yo un muchacho con un libro publicado en secreto y otro con seudónimo. Ante una pregunta sobre mis autores preferidos, tomé la palabra y, desafiando la timidez, que me impedÃa mantener la sintaxis de una frase entera, emprendà el elogio de la prosa desvaÃda de un poetastro que dirigÃa la página literaria de un diario porteño. Quizá para renovar el aire, Borges amplió la pregunta:

—De acuerdo —concedió—, pero fuera de Fulano, ¿a quién admira, en este siglo o en cualquier otro?

—A Gabriel Miró, a AzorÃn, a James Joyce. —contesté.

¿Qué hacer con una respuesta asÃ? Por mi parte no era capaz de explicar qué me agradaba en los amplios frescos bÃblicos y aun eclesiástios de Miró, en los cuadritos de AzorÃn ni en la gárrula cascada de Joyce, apenas entendida, de la que levantaba, como irisado vapor, todo el prestigio de hermético, de lo extraño y de lo moderno. Borges dijo algo en el sentido de que sólo en escritores entregados al encanto de la palabra encuentran los jóvenes literatura en cantidad suficiente. Después, hablando de la admiración por Joyce, agregó:

—Claro, es una intención, un acto de fe, una promesa. La promesa de que les gustará —se referÃa a los jóvenes— cuando lo lean. |

|

I believe my friendship with Borges stems from our first conversation, which occurred in 1931 or 32, in transit between San Isidro and Buenos Aires. Borges was at that time one of our best-known young authors; I was a boy with one book published in secret and another one pseudonymously. Asked a question about my favorite authors, I took the floor and (defying the shyness which was making it difficult for me to get a coherent sentence out), set off on an unfocussed panegyric in praise of the poetaster who edited the literary supplement of a Buenos Aires newspaper. Perhaps to clear the air, Borges expanded his question: -- Certainly -- he admitted -- but outside of Fulano, whom do you admire, in this century or some other? -- Gabriel Miró, AzorÃn, James Joyce. -- I replied. What to do with such a response? For my own part, I would not have been able to explain what appealed to me in the cool, spacious, biblical -- even ecclesiastical -- works of Miró, in the rustic tomes of AzorÃn, nor in the garrulous cascade of Joyce -- even given, as I was taking for granted, like a rainbow in the air, all the prestige of the hermetic, the strange and modern. Borges said something to the effect that only in authors committed to the bewitching effect of the word do young people encounter literature in sufficient quantity. Later, speaking of my admiration for Joyce, he added: -- Clearly, it's an intention, an act of faith, a promise. The promise that they will like it -- referring here to young people -- when they read it.

|

An imposing brick of a book arrived in the mail yesterday; it is Adolfo Bioy Casares' Borges, 1,600 pages excerpted (by Bioy Casares' literary executor Daniel Martino, in collaboration with the author at the end of his life and posthumously) from the 20,000 pages of diary left in his estate. Bioy Casares began keeping his diary in 1947; the above is from a brief foreword titled "1931 - 1946" which appears to have been written much later.

An imposing brick of a book arrived in the mail yesterday; it is Adolfo Bioy Casares' Borges, 1,600 pages excerpted (by Bioy Casares' literary executor Daniel Martino, in collaboration with the author at the end of his life and posthumously) from the 20,000 pages of diary left in his estate. Bioy Casares began keeping his diary in 1947; the above is from a brief foreword titled "1931 - 1946" which appears to have been written much later.I had not realized Bioy Casares was so much younger than Borges; had always assumed they were about the same age. (I have not yet read anything by Bioy Casares either by himself or in collaboration with Borges; I know him mainly from mentions in Borges' stories.) When they met in 1931, Borges would have been in his early thirties and Bioy Casares a teenager -- Borges was a mentor more than a peer -- this totally changes my picture of the dinner at the beginning of "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius," where Bioy Casares recalls the teaching of a heresiarch of Uqbar, the first intrusion of Tlön into the life of the narrator. There is a bit of meat in this brief exchange. I'm not sure what to make of Borges' statement about the "bewitching effect of words" -- sounds a bit like hand-waving to keep his young interlocutor from having to explain himself and feel embarrassed. I don't know Miró or AzorÃn at all; I'm wondering if the trio of authors Bioy Casares names here is meaningful or if it is just the first three names that come to mind as he is struggling to master his timidity. Totally unsure about my reading "like a rainbow in the air," I don't know what the meaning is here. The picture of Borges here is very pleasing; and it's such an exciting thing to imagine this meeting, in 1931, with the whole history of their literary collaboration as yet unborn.

posted morning of March 27th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Borges

|  |

Sunday, March 28th, 2010

|

Años depsués, Taylor visitó las cárceles de ese reino; en la de Nithur el gobernador le mostró una celda, en cuyo piso, en cuyos muros, y en cuya bóveda un faquir musulmán habÃa diseñado (en bárbaros colores que el tiempo, antes de borrar, afinaba) una especie de tigre infinito. Ese tigre estaba hecho de muchos tigres, de vertiginosa manera; lo atravesaban tigres, estaba rayado de tigres, incluÃa mares e Himalayas y ejércitos que parecÃan otros tigres. El pintor habÃa muerto hace muchos años, en esa misma celda; venÃa de Sind o acaso de Guzerat y su propósito inicial habÃa sido trazar un mapamundi. | | Years later, Taylor visited the prisons of this district; in the one at Nithur, the governor showed him a cell on whose walls, on whose floor, on whose vault a Muslim fakir had laid out (in barbarous colours which time, not yet ready to wipe them clean, was refining) a sort of infinite tiger. This tiger, this vertiginous tiger, was composed of many tigers; tigers ran across it and radiated outward from it; it contained seas and Himalayas and armies which appeared as other tigers. The painter had died many years before, in this same cell; he came from Sindh or perhaps from Gujarat, and his initial intention had been to draw a map of the world. |

"The Zahir"

|

Más de una vez grité a la bóveda que era imposible descifrar aquel testo. Gradualmente, el enigma concreto que me atareaba me inquietó menos que el enigma genérico de una sentencia escrita por un dios. ¿Qué tipo de sentencia (me pregunté) construirá una mente absoluta? Consideré que aun en los lenguajes humanos no hay proposición que no implique el universo entero; decir el tigre es decir los tigres que lo engendraron, los ciervos y tortugas que devoró, el pasto de que se alimentaron los ciervos, la tierra que fue madre del pasto, el cielo que dio luz a la tierra. Consideré que en el lenguaje de un dios toda palabra enunciarÃa esa infinita concatenación de los hechos, y no de un modo implÃcito, sino explÃcito, y no de un modo progresivo, sino inmediato. Con el tiempo, la noción de una sentencia divina parecióme pueril o blasfematoria. Un dios, reflexioné, sólo debe decir una palabra, y en esa palabra la plenitud. Ninguna voz articulada por él puede ser inferior al universo o menos que la suma del tiempo. | |

More than once, I screamed at the vaulted ceiling that it would be impossible to decipher this testament. Gradually, the immediate riddle confronting me came to trouble me less than the general riddle: a sentence written by a god. What sort of sentence (I asked) would an absolute consciousness construct? I reflected: even in the languages of humanity there is no proposition which does not imply the entire universe; to speak of the tiger is to speak of the tigers which begot it, the deer and turtles which it ate, the pasture on which the deer nourished themselves, the earth which was mother of the pasture, the heavens which gave forth light onto the earth. I reflected: in the language of a god, every word must bespeak this infinite concatenation of things, not by implication, but explicitly; not in a progressive manner, but in the instant. With time, the notion of a divine sentence came to appear puerile, blasphemous. A god, I reasoned, would only be able to say a single word, and in this word would be everything. No voice, no articulation of his could be inferior to the universe, could be less than the sum of all time.

|

"The God's Scripture"*

The twenty-centavo piece which falls into Borges' palm and destroys him in "The Zahir," is the same entity which Tzinacán labors mightily to comprehend (and which destroys him) in "The God's Scripture." (Notice Borges says at the beginning of his tale, "I am not the man I was then, but I am still able to recall, and perhaps recount, what happened. I am still, albeit only partially, Borges" -- Tzinacán closes his story saying, "I know I shall never speak those words, because I no longer remember Tzinacán.")

What I remembered about "The Zahir" before I reread it today, was the broad arching theme of it, the object which is a manifestation of God, which cannot be forgotten, which drives people mad; I had totally forgotten what a great story it is, the characters, the local flavor of Buenos Aires.

* Update -- Thinking further, I would rather translate this story's title -- "La escritura del dios", which Hurley renders literally as "The Writing of the God" -- simply as "Scripture".

posted evening of March 28th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about The Aleph

|  |

Tuesday, March 30th, 2010

I've been posting here and there lately (and for the past 7 years!) under the label Translation, without ever really defining very clearly what I am trying to do with that. So here is a little gesturing in that direction. I really enjoy reading books in languages that I'm not fluent in -- not sure exactly what it is, but somehow the neural pathways that light up when I read a page of German or Spanish*, repeat the words under my breath, and transform them internally into words and concepts I understand, are pleasurable ones. And I frequently admire translations that I read, the best ones and the lesser as well, and enjoy picking them apart and seeing where and why they diverge from the original. So translation seemed like a pretty natural thing for me to try my hand at. I'm certainly not going for any kind of authorative version in my translations -- sometimes I spend some time on refining them and getting them to sound good, other times I try and leave them raw; but generally what I'm trying to do is to get across my experience of reading the text -- this is after all a blog about reading -- and to intensify the act of reading. I remember seeing somewhere a statement that translation is a form of reading, and liking it. I've been emboldened lately by Andrew Hurley's statement, in his Note on the Translation of Borges' Collected Fictions, that there is no such thing as a definitive translation of a text -- I'm familiar with this sentiment but it moved me to see it voiced by Hurley, whose translations seem to me some of the best I've ever read. Hurley cites Borges' "Versions of Homer" and "The Translators of the 1001 Nights" -- "The very idea of the (definitive) translation is misguided, Borges tells us; there are only drafts, approximations."

* (And I ought to start learning another language to be not-fluent in...)

posted evening of March 30th, 2010: 5 responses

➳ More posts about Projects

|  |

Saturday, April 10th, 2010

This is the second story in The black sheep and other fables -- the story of which Isaac Asimov says (and I'm dying to know now whether this book has been published in translation, or if Asimov reads Spanish...)* that after reading it, "you will never be the same again."

In the jungle there once lived a monkey who wanted to write satire.He studied hard, but soon realized that he did not know people well enough to write satire, and he started a program of visiting everyone, going to cocktails and observing, watching for the glint of an eye while his host was distracted, a cup in his hand. As he was most clever and his agile pirhouettes were entertaining for all the other animals, he was received well almost everywhere; and he strove to make it even moreso. There was no-one who did not find his conversation charming; when he arrived he was fêted and jubilated among the monkeys, by the ladies as much as by their husbands, and by the rest of the inhabitants of the jungle too, even by those who were into politics, whether international, domestic or local, he invariably showed himself to be understanding -- and always, to be clear, with the aim of seeing the base components of human nature and of being able to render them in his satires. And so there came a time when among the animals, he was the most advanced student of human nature; nothing got by him. Then one day, he said: I'm going to write against thievery, and he went to see the magpies; and at first he went at it with enthusiasm, enjoying himself and laughing, looking up with pleasure at the trees as he thought about what things happen among the magpies -- but then on second thought, he considered the magpies who were among the animals who had received him so pleasantly -- especially one magpie, and that they would see their portrait in his satire, however gently he wrote it.. and he left off doing it. Then he wanted to write about opportunists, and he cast his eye on the serpent, who by whatever means (auxiliary to his talent for flattery) managed always to conserve, to trade, to increase his posessions... But then some serpents were friends of his, and especially one serpent; they would see the reference. So he left off doing it.

Then he thought of satirizing compulsive work habits, and he turned to the bee, the bee who works dumbly and without knowing why or for whom; but for fear of offending some of his friends of this genus, and especially one of them, he ended up comparing them favorably to the cicada, that egotist who will do nothing more than sing, sing, who thinks himself a poet... and he left off doing it.

Then it occurred to him, he could write against sexual promiscuity, and he directed his satire against the adulterous hens who strut around all day restlessly looking for roosters; but then some of them had received him well, he feared hurting them, and he left off doing it.

In the end he came up with a complete list of human failings and weaknesses, and he could not find a target for his guns -- they were all failings of his friends who had shared their table with him, and of himself. At that moment he renounced his writing of satire, and began to teach mysticism and love, this type of thing; but this made people talk (you know how it is with people), they said he had gone crazy, they no longer received him as gladly or with such pleasure.

* Yep, looks like it was published in English in 1971.

posted evening of April 10th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about The Black Sheep and other fables

|  |

|

While I'm thinking of it, another story I really enjoy from The Black Sheep and other fables:

At first, faith moved mountains only as a last resort, when it was absolutely necessary, and so the landscape remained the same over the millennia.But once faith started propagating itself among people, some found it amusing to think about moving mountains, and soon the mountains did nothing else but change places, each time making it a little more difficult to find one in the same place you had left it last night; obviously this created more problems than it solved. The good people decided then to abandon faith; so nowadays the mountains remain (by and large) in the same spot. When the roadway falls in and drivers die in the collapse, it means someone, far away or quite close by, felt a light glimmer of faith.

posted evening of April 10th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Augusto Monterroso

| More posts about Translation

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

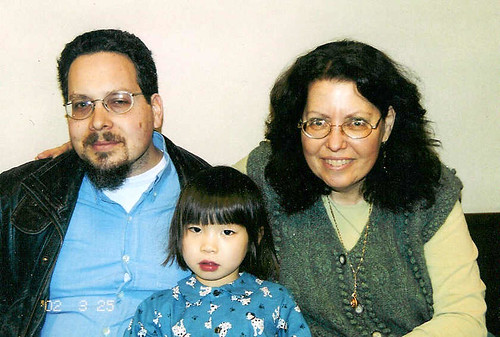

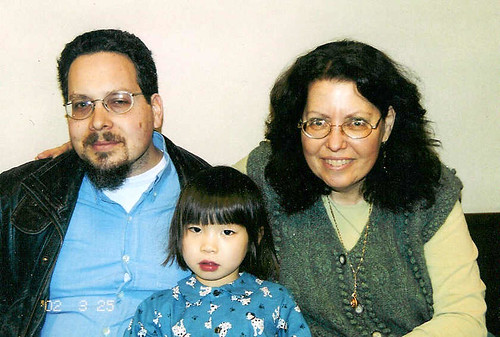

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |