|

|

Thursday, September 20th, 2007

I went over to Montclair Book Center today and picked up a wealth of Pamuk: The White Castle, The New Life, The Black Book, and his new collection of essays, Other Colors. First thing I read was his notes on My Name is Red, written during an airplane flight immediately after he finished checking the final copy. He says he is worried about the outer story of the novel, "that the mystery plot, the detective story, was forced, and that my heart wasn't in it, but it would be too late to make changes." I can totally understand him feeling that way -- it seems to me like it must have been a huge amount of work integrating the two stories and getting the product to flow naturally. He offers his aplogies to "my poor miniaturists" for "the intrusion of a political detective plot that would make my novel easy to read." But he doesn't need to worry about it (well obviously, duh, he won the Nobel Prize...), the outer story not only makes the book easier to read, but adds layers of meaning and beauty to it. I posted at KIDLIT about reading some of these essays to Sylvia.

posted evening of September 20th, 2007: Respond

➳ More posts about The New Life

|  |

Saturday, March 8th, 2008

Never use epigraphs -- they kill the mystery in the work!

-- Adli

If that's how it has to die, go ahead and kill it; then kill the false prophets who sold you on the mystery in the first place!

-- Bahti

This morning I started reading The Black Book, by Orhan Pamuk -- and as I read the first pages I had the immediate sensation of having come home. Now the context for this is having felt really strongly drawn into the writing in Snow and My Name is Red, and digging Other Colors to the point of identifying the speaker of the words as myself; and then being less impressed by The New Life and The White Castle. Now this book is definitely holding out promise of having been written by the mature Pamuk, the one who entrances me utterly. (It was written before The New Life, which surprises me a little.) What really struck me was the intensity of my reaction -- the palpable shock of recognition I felt starting from the very first sentence. ("Rüya* was lying facedown on the bed, lost to the sweet warm darkness beneath the billowing folds of the blue-checked quilt.") I've only even known who this guy is for less than a year but I've apparently given him lease on a substantial portion of my cerebral cortex. Not too much organized yet to say about this particular book, I'm just starting it; but it does seem worth noting that the switching back and forth between first person and third person narration is so smooth and natural, it took me a few paragraphs to even figure out it had happened, the first couple of times he did it. Subtly beautiful. It took longer to figure out what was going on with Chapter Two, which is a column written by the narrator's cousin, but once I had gotten that it was good. Pamuk seems to be anticipating me -- when I have a question about some detail of the plot it seems to be getting answered within 2 or 3 pages of where it arises. It's just really hard to resist giving a long quote. Here is a bit from the first page: Languid with sleep, Galip gazed at his wife's head: Rüya's chin was nestling in the down pillow. The wondrous sights playing in her mind gave her an unearthly glow that pulled him toward her even as it suffused him with fear. Memory, Celâl had once written in a column, is a garden. Rüya's gardens, Rüya's gardens... Galip thought. Don't think, don't think, it will make you jealous! But as he gazed at his wife's forehead, he still let himself think.He longed to stroll among the willows, acacias, and sun-drenched climbing roses of the walled garden where Rüya had taken refuge, shutting the doors behind her. But he was indecently afraid of the faces he might find there: Well, hello! So you're a regular here too, are you? It was not the already identified apparitions he most dreaded but the insinuating male shadows he could never have anticipated: Excuse me, brother, when exactly did you run into my wife, or were you introduced?... And it goes on from there -- this seductive prose (in Maureen Freely's translation, and hooray! for Maureen Freely, say I) won't let me go. Freely has also written an afterword to the novel, which gives some historical context to the events of the story, and talks about her process of translating Turkish.

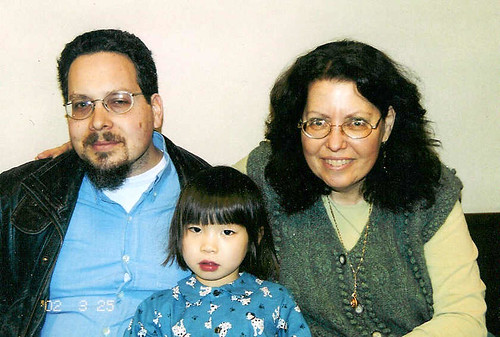

*Rüya is the name of Pamuk's daughter, in addition to this character's name; when Sylvia was looking over my shoulder this morning she said "Rüya, like in 'off the floor'!" "Off the floor" is a game Pamuk and his daughter play in the essay "When Rüya is Sad", and which Sylvia has appropriated for her own.

posted evening of March 8th, 2008: Respond

➳ More posts about Orhan Pamuk

|  |

Sunday, March 16th, 2008

That fantastic epigraph I quoted, that Pamuk uses for the head of Chapter 1 of The Black Book, turns out to come from inside the book, from a column of Celâl's (specifically, Chapter 8, "The Three Musketeers"). Oops -- now I feel a little embarrassed about searching for the source of this marvelous line. Pamuk has been playing tricks on me again! I don't think I have seen this from any other author, the way he uses epigraphs and even dedications that are internal to the book. Kind of makes my head spin.

posted evening of March 16th, 2008: Respond

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

...this eye was there to ease my passage into this "metaphysical experiment", which I would later decide bore the hallmarks of a dream; it was there, above all, to be my guide.Utter silence. I knew at once that the experiment on which I was about to embark had something to do with that thing my profession had taken away from me and everything to do with that emptiness I felt inside me. A man's nightmares are never so real as when he's starved of sleep! But this was not a nightmare; it was sharper, clearer, almost mathematical in its precision. I know I'm empty inside. This was what I was thinking... the thought lingered. Inside it was an open door; I walked toward it, and like the English girl who followed a rabbit through a gap in the hedge, I soon found myself falling into a new world.

... What I created first was not the eye, first I created Him, the man I wished to be. It was He -- the man I wished to be -- who stepped back to cast His stifling and terrifying gaze upon me.

I am wondering about Celâl. At first The Black Book seemed to be mainly about Galip, with Celâl a minor side character, present (or "not present") for comic effect. But his essays are really starting to resonate.

posted evening of March 16th, 2008: Respond

|  |

Friday, March 21st, 2008

No need to read Ibn Khaldun; those charged with this task would quickly guess that the only way forward was to rip away our memories, our past, our history, leaving us with nothing but our misfortunes.... But later on, the Western bloc's "humanitarian wing" had declared this reckless initiative too dangerous...and switched to a gentler approach that promised longer-lasting results: the new plan was to erode our collective memory with movie music.Church organs, pounding out chords of a fearful symmetry, women as beautiful as icons, the hymnlike repetition of images, and those arresting scenes sparkling with drinks, weapons, airplanes, designer clothes -- put all these together and it was clear that the movie method proved far more radical and effective than anything missionaries had attempted in Africa and Latin America. (These long sentences of his were well-rehearsed, Galip decided. Who else had had to hear them, his neighbors? His colleagues at work? His mother-in-law? The people sitting next to him in a dolmuş?) It was in the Şehzadebaşı and Beyoğlu movie theaters that they set their plan into action; before long, hundreds of people had gone utterly blind. Viewers who sensed the terrible plot that was being perpetrated on them and rebelled with angry cries were quickly silenced by policemen and mad doctors. When the children of today showed a similar reaction -- when they were blinded by the proliferation of new images -- they were fobbed off with new prescription glasses. But there were always a few who refused to go away quietly. A while ago, he'd been walking through another neighborhood not far from here around midnight when he'd seen a sixteen-year-old boy pumping futile bullets into a movie billboard -- and immediately he'd understood why. Another time, he'd seen a man at the entrance to a theater with two cans of gasoline swinging from his hands; as the bouncers roughed him up, he kept demanding that they give him his eyes back -- yes, the eyes that could see the old images.... We'd all been blinded, every last one of us, every last one...

(Want to write about this quotation in a minute, but I am being called away by Sylvia to read Pippi Longstocking just at the moment. Back in a little while.)

A few observations: Rüya's ex-husband's (I believe he has not been named, though a few of his aliases surfaced in a previous chapter) sort of anti-semitic rant weaves uncertainly between weird craziness and poetry -- reminds me in a way of the Islamicists in Snow. Galip's parenthetical aside is just masterful. (There is a similar aside a few paragraphs later where Galip describes the man as "sinking into the pages of his encyclopedic metaphor".) I like the coincidence here with Blindness -- I wouldn't necessarily give it a whole lot of weight but I think this passage might be a good one to have in mind when rereading Saramago. Also -- not sure if this is valid but I see vaguely a reflection of the remarks that Jeremiah Wright is being pilloried for these days.

posted evening of March 21st, 2008: Respond

➳ More posts about The Movies

|  |

Saturday, March 22nd, 2008

Another jarring moment of recognition in The Black Book -- in the story Galip is telling in chapter 15, about a Turkish bachelor who obsessively loves Proust, he says, "like all Turks who come to love Western authors that no one else reads, he went from loving Proust's words to believing that he himself had written them." I'm a little blown away by this identity-with-the-author thing that I've come up with to describe my experience reading Pamuk -- it is very much Pamuk's own trope; but it seems to me I started talking about it before I had happened on Pamuk's use of it. This probably means he is describing a universal experience -- and thinking back now that I've constructed this way of relating to the book, I can see how it applies to some reading I've done in the past -- the coincidence just seems pretty shocking to me, that I would hit on it to talk about this particular author, whose work turns out to contain it.

I am a little curious about whether each of the alternate chapters which is a column by Celâl, is the column which is printed on the day of the following chapter. This would mean that each of the narrative chapters takes place a day after the previous one, which I'm not sure that would work. ... And indeed it does not work: Chapter 17 takes place immediately after Chapter 15. Oh well, another hypothesis down the drain.

posted evening of March 22nd, 2008: Respond

|  |

Saturday, March 29th, 2008

How to enter the secret world of second meanings, how to break the code? He was standing on the threshold -- joyful and expectant -- but he had no idea how to cross it. Chapter 19 of The Black Book, "Signs of the City", seems in a way like the key to the story -- in a very meta- way, that is to say, being as Galip is spending this chapter discovering the "key" to the story he is pursuing, and thereby descending into paranoia. [Caveat lector: this is my understanding of the story at the moment, halfway through; certainly subject to revision.] I'm particularly interested in pages 213 - 219, Galip's hallucinatory walk through Nişantaşı central Istanbul, which culminates in his complete identification with Celâl. Read some extensive quotation and light analysis below the fold.

As he walked across the bridge, gazing idly into the Sunday crowds, he was suddenly certain that he was on the verge of solving a riddle that had been vexing him for years without his even being aware of it. In some deep and dreamlike way he was also aware that this was an illusion, but he seemed able to hold the contradictory thoughts in his mind with ease. Throughout the book, there have been suggestions of a riddle for Galip to unlock -- on the most superficial level, he needs to figure out where Rüya is and where Celâl is. He's become convinced they're together, and the question Why? poses itself; also there are various paranoid threads running through the story about the history of Istanbul and the state of the modern world, and about Galip's family. Galip's relationship with Celâl parallels the reader's relationship with Pamuk. He stared at them for the first time, carefully reading their logos. For a moment it seemed to him that these were the words and letters that would lead him to the other world, the true world, and his heart leaped. ... All contained the key to the mystery, but what was the mystery? This is an intricate game: you can see that Galip is going insane; but you totally sympathize because you are feeling that the words you are reading are the ones that will lead you to the true world. You know Pamuk is hip to that and it's a joke you're sharing with him, but on some level you gotta wonder... Then you say "No, that's crazy" and turn the page. He surveyed the ramshackle shops lining the crooked pavements: These garden shears he saw before him, these star-spangled screwdrivers, NO PARKING signs, cans of tomato paste, these calendars you saw on the walls of cheap restaurants, this Byzantine aqueduct festooned with Plexiglas letters, the heavy padlocks hanging from the metal shop shutters -- they were all signs crying out to be read. Pamuk can imbue lists of objects with meaning like nobody else except maybe Pynchon. [Further: Maureen Freely in her afterword notes that "mesmerizing lists" are a characteristic of Turkish prose, and are difficult to translate successfully -- props to Ms. Freely for the job she does here, and maybe I should seek out more Turkish prose.] The list of objects Galip sees in front of the junk dealer on the next page, similarly great. Speaking of which, He named them all, enunciating each word with care, and studied them closely. It was not the objects that bewitched him, it was the order in which they'd been arranged. ... It reminded him of the vocabulary tests when he was studying English and French: sixteen familiar objects, waiting to be renamed in a new language. Galip wanted to call out the answers: Pipe, record, telephone, shoes, pliers....But they made no secret of their other meanings; that's what Galip found shocking. Galip's search for a riddle and an answer is coming to a head here as he begins to see meaning (and meaning directed at him) in everything he looks at. But when she reached the end of these vile translations, these same objects did transport Rüya and her detective to a new world, whereas all Galip could do was entertain the hope that he might one day see it. Again: playful flirtation with the idea of Galip as a frustrated reader looking for consummation in the text. Or: When he stepped onto Atatürk Bridge, Galip had resolved to look only at faces. Watching each face brighten at his gaze, he could almost see question marks bubbling from their heads -- the way they did in the Turkish versions of Spanish and Italian photo novels -- but they vanished in the air without leaving a trace. His walk ends after he crosses the second bridge (shades of Through the Looking Glass!); he is sitting in a coffeehouse when he finds his answer and his transformation is realized. After ordering tea from the boy, he took Celâl's column out of his coat pocket and began to read it again from the beginning. The letters, words, and sentences had not changed in any way, but as his eyes traveled over them, they suggested ideas that Galip had never before entertained; these were not Celâl's ideas but his own, though in some odd way he saw them reflected in the text.... He listed all his clues in tiny letters, and when he came to the end of the page, he thought, How easy that was! and then, Since I am now certain that Celâl and I think alike, I must study more faces! This certainty is Galip's ticket to the new world, the secret world of second meanings. It plays out in interesting ways for the rest of the chapter as his fantasy overlays the neighborhood he is moving in, after he returns to Nişantaşı.

↻...done

posted evening of March 29th, 2008: Respond

|  |

Sunday, March 30th, 2008

Google Maps is just about the greatest thing ever. (Well ok, there are better things out there. But still.) I am over there now, figuring out what Galip's movements through Nişantaşı, Beyoğlu, Teşvikiye, and other Istanbul locations look like spatially. I can see how the Golden Horn separates these neighborhoods from central Istanbul, where are the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara in relation to the city, where the Atatürk and Galata bridges are; just great! It took a moment to see I was mistaken about Galip's walk in chapter 19 being through Nişantaşı; and looking back to the chapter I see he was walking near the Süleymaniye Mosque, which is in the center of the city, south of the Golden Horn; page 223 has him walking north, back towards Nişantaşı.

posted afternoon of March 30th, 2008: Respond

|  |

Saturday, April 5th, 2008

...as he read, he identified first with the usher, then with the brawling audience, then with the çörek maker, and finally -- good reader that he was -- with Celâl.-- The Black Book

A couple of jottings in furtherance of my essay idea:

- Identity confusion is important in Pamuk.

- I started to formulate this statement while I was reading Other Colors, and have since seen it borne out in The White Castle, The New Life, and especially The Black Book.

- Does this statement also apply to Snow and My Name is Red, which I read before it occurred to me? (beyond the obvious detective-story aspects of Red) -- the answer may well be yes but I think I would need to reread them with this in mind, to be sure. If not, it might seem appropriate to think of this as something Pamuk had "outgrown".

- The confusion that I'm talking about is (frequently) a confusion between the roles of Author and Reader. So it's an easy step to take, to confuse yourself-as-reader with Pamuk-as-author. Or so I think.

- As a side note, I wonder how this plays into my impression of these 5 novels, which is that each of them is written in a distinctly different style and voice -- though I think I can hear shades of the same voice underlying each -- if Pamuk is serious about giving up his identity when he writes that would help explain the differences. An alternate explanation is that there are four different translators involved in creating English versions of these five books -- only Maureen Freely has two translations. But I don't think those two are particularly more similar to each other than any other pair.

- I think the experience of losing track of one's identity while reading a story is a wonderful thing; it might be the primary reason I read novels. Understanding this is something I am taking away from reading Pamuk. Is this the same as saying "I read for escape from my everyday life", which seems banal and not really worth thinking about at length the way I have been doing? In Pamuk's novels it seems to be doing a lot more work than that.

- What larger ideas if any does this lead to? How is the beauty of Pamuk's books explicable in these terms? Would such an explication be "criticism"? (Note: I've had an ongoing conversation with myself about what is criticism, and is it something I would be able to write, for a while now.)

posted evening of April 5th, 2008: Respond

➳ More posts about Other Colors

|  |

You became someone else when you read a story -- that was the key to the mystery. The chain of mystery in The Black Book is spiralling wider and wider in Chapter 24. The story seems to have taken Galip's paranoid break with reality smoothly in stride and assimilated that into the "reality" of the book. Galip's identification with Celâl is a done deal; and now we are seeing Celâl as having discarded his own identity in favor of Rumi's*. In addition Celâl has asserted in the previous chapter, that being able to tell stories, to command the attention of an audience and (I am reading in) thus to weaken your audience members' identities and to intermix your own self into them, is a primary element of human existence, something without which a person is anguished and "helpless in the face of the world!"Meanwhile the unknown caller is competing with Galip for Celâl's identity, and Galip has a moment of suspicion that he has been lured into "a deadly trap."

*I have not read nearly enough Rumi -- I reckon I am going to be missing a lot of nuance in this portion of the book. The story about Shams of Tabriz in Chapter 22, for example, is widely divergent from what I read about him in the closest reference work to hand; I don't know what to make of this. ...Well here is a program about Rumi which speaks of a disputed account of Shams being murdered by Rumi's disciples. So the Wikipædia article is just incomplete I guess. (The Wikipædia article on Rumi does mention the murder, and does not even say that it is disputed.) That program also links to some readings from Rumi in Persian and in translation.

posted evening of April 5th, 2008: Respond

| More posts about The Black Book

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |