|

|

Saturday, March 17th, 2018

Once upon a time, not so very long ago and yet not so recently, everything imitated everything else, and thus, if not for aging and death, man would've never been the wiser about the passage of time.

It seems to me like this blog came into its own when I started reading Snow in 2007. While I was reading My Name is Red (directly afterwards), I did a Google search for the lovely quote above concerning aging and death, and happened on Rafael Carpintero's overview of his translation workshop, "Un autor en busca de tres traductores". Alas the article was in Spanish, a language I did not know, at the time, sufficiently to follow the full article.Well in the intervening ten years I've learned Spanish and have had occasional success as a translator... I'm currently starting to read The New Life in Carpintero's Spanish translation, and was led back to "Un autor en busca de tres traductores" -- long story short, I've gotten in touch with Carpintero and have obtained his permission to translate the article!

posted morning of March 17th, 2018: 1 response

➳ More posts about Orhan Pamuk

|  |

Sunday, March 11th, 2012

The Pacific is really a tranquil ocean now, as white as a large basin of milk. The waves have warned it that the earth is approaching. I try to measure the distance between two waves. Or is it time that separates them, not distance? Answering this question would solve my own mystery. The ocean is undrinkable, but it drinks us. ... What will the new day illuminate? I'd like to give you a very fast answer because I'm losing the words to tell you, the survivors, this tale.

I started looking at Carlos Fuentes' Destiny and Desire (tr. Edith Grossman) this weekend -- I must say this book is going to take me a long, long time to read. It is a thick enough book to be sure, more than 500 pages; but what is slowing it down for me is the inability to start anywhere else besides the first page when I pick the book up. I've read the opening pages several times over now and they are not losing any of their appeal.Fun bit of intertextuality -- last thing I remember reading that is narrated by a murder victim, was the opening chapter of My Name is Red. So Destiny and Desire (a title I find corny, oh well) is starting out with a very positive association... Fuentes is a bit of a hole in my literary experience -- I made a couple of stabs fairly recently at Artemio Cruz but got nowhere -- this new book sure seems at first impressions like it will be a good place to start.

posted evening of March 11th, 2012: Respond

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

Tuesday, August 19th, 2008

BBC Radio 4 broadcast My Name is Red on its Classic Serial program -- it sounds from Gillian Reynolds' note like it was a fantastic adaptation. I didn't know about it until just now, which is too bad because you can listen to the latest episode online for a week after it airs. Hopefully they will rebroadcast it before too long, I'd love to hear it.

posted evening of August 19th, 2008: 2 responses

|  |

Thursday, July 31st, 2008

McGaha's observations about My Name is Red mostly just reinforce my own thoughts about that book, so not a lot worth posting about this chapter. He included a couple of details in his summary that I totally don't remember and may not have gotten when I was reading the book, like the Erzurumis strangling the storyteller, and the storyteller's chapters dividing the book into sections; good stuff to look for when rereading. A great line: Pamuk has said he had so much fun writing My Name is Red that his "inner modernist" kept wagging his finger and reminding him that he was a serious writer and needed to be intellectual and literary. Also I found really interesting, McGaha's discussion of how My Name is Red is similar to, and opposite to, The Black Book.

posted evening of July 31st, 2008: Respond

➳ More posts about Autobiographies of Orhan Pamuk

|  |

Monday, July 7th, 2008

My Name is Red is set in 1591 -- I am reading Pamuk's essay on "Bellini and the East," from Other Colors, and find out about Bellini's portrait of Sultan Mehmet II, dated 1480. I don't remember any specific reference to this painting in My Name is Red, but I am sure now that there must have been some -- I must have passed over it as something unfamiliar, not bothered to look it up. My Name is Red is set in 1591 -- I am reading Pamuk's essay on "Bellini and the East," from Other Colors, and find out about Bellini's portrait of Sultan Mehmet II, dated 1480. I don't remember any specific reference to this painting in My Name is Red, but I am sure now that there must have been some -- I must have passed over it as something unfamiliar, not bothered to look it up.

Pamuk says, The portrait has spawned so many copies, variations, and adaptations, and the reproductions made from these assorted images have gone on to adorn so many textbooks, book covers, newspapers, posters, banknotes, stamps, educational posters, and comic books, that there cannot be a literate Turk who has not seen it hundreds if not thousands of times. It seems logical that this painting would have been an important element of the debate about artistic style and representation in the Ottoman empire, a century after it was painted. I should keep an eye out for this next time I read the book.

(I see that with this entry, Pamuk becomes the first author about whom I've written 100 posts. Not exactly sure what to make of that, beyond that I'm totally gaga about his writing.)

posted morning of July 7th, 2008: Respond

➳ More posts about Other Colors

|  |

Sunday, July 6th, 2008

At the end of the second chapter of Autobiographies of Orhan Pamuk I learn that Other Colors, ostensibly a translation of Pamuk's 1999 collection Öteki Renkler: Seçme Yazılar ve Bir Hikaye, is actually a separate collection, with only about a third of the contents taken from the older book.* All the essays on Turkish literature and politics were omitted from the English version. Replacing them were... assessments of the works of authors he admires -- ranging from Fyodor Dostoyevsky to Salman Rushdie -- ...others are autobiographical or contain thoughtful reflections on his own novels. This is surprising to me. I like the selection in Other Colors; but I'd be very interested to read Pamuk's essays on Turkish literature and politics as well. McGaha quotes a passage from Pamuk's essay (which he had written in 1974, at the outset of his career) on the Turkish author Oğuz Atay: Pamuk argues that critics were bewildered by the novelty of Atay's novels, in which the author's voice and attitude, his peculiar tone of intelligent sarcasm, were more important than plot or character development. What is most distinctive about these novels is their style:When the novelist puts the objects that he saw into words in this or that way, what he is doing is a kind of deception that the ancients called "style," manifesting a kind of stylization. There are deceptions every writer uses, like a painter who portrays objects. This is the only way I can explain Faukner's fragmetation of time, Joyce's objectification of words, Yaşar Kemal's drawing his observations of nature over and over. Talented novelists begin writing their real novels after they discover this cunning. From the moment that we readers catch on to this trick, it means that we understand a little bit of the novelistic technique, what Sartre called "the writer's metaphysics." This passage seems pretty key to an understanding of My Name is Red, and how it fits in with Pamuk's other novels. I'm sorry to see neither of Atay's novels has been translated into English.

* A little thought makes it obvious that many of the essays in Other Colors could not have appeared in the earlier collection, dealing as they do with events occuring in 2005 and later. My grasp of Pamuk's timeline was not as firm when I first looked at this book as it is now. I also went back just now to reread the preface, which makes clear that this is a separate work from the earlier collection. Look at its beautiful final paragraph: I am hardly alone in being a great admirer of the German writer-philosopher Walter Benjamin. But to anger one friend who is too much in awe of him (she's an academic, of course), I sometimes ask, "What is so great about this writer? He managed to finish only a few books, and if he's famous, it's not for the work he finished but the work he never managed to complete." My friend replies that Benjamin's œuvre is, like life itself, boundless and therefore fragmentary, and this was why so many literary critics tried so hard to give the pieces meaning, just as they did with life. And every time I smile and say, "One day I'll write a book that's made only from fragments too." This is that book, set inside a frame to suggest a center that I have tried to hide: I hope that readers will enjoy imagining that center into being.

posted afternoon of July 6th, 2008: Respond

➳ More posts about Michael McGaha

|  |

Thursday, September 20th, 2007

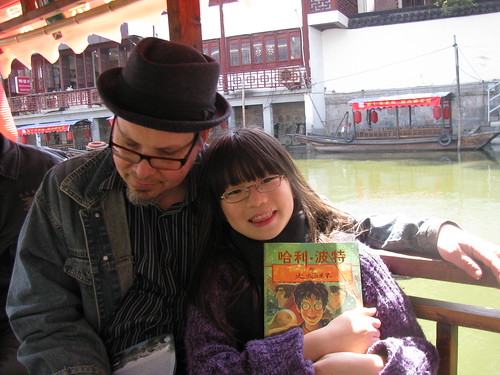

I went over to Montclair Book Center today and picked up a wealth of Pamuk: The White Castle, The New Life, The Black Book, and his new collection of essays, Other Colors. First thing I read was his notes on My Name is Red, written during an airplane flight immediately after he finished checking the final copy. He says he is worried about the outer story of the novel, "that the mystery plot, the detective story, was forced, and that my heart wasn't in it, but it would be too late to make changes." I can totally understand him feeling that way -- it seems to me like it must have been a huge amount of work integrating the two stories and getting the product to flow naturally. He offers his aplogies to "my poor miniaturists" for "the intrusion of a political detective plot that would make my novel easy to read." But he doesn't need to worry about it (well obviously, duh, he won the Nobel Prize...), the outer story not only makes the book easier to read, but adds layers of meaning and beauty to it. I posted at KIDLIT about reading some of these essays to Sylvia.

posted evening of September 20th, 2007: Respond

➳ More posts about The New Life

|  |

Sunday, September 16th, 2007

Chapter 58: one of this book's longest chapters; a 20-page crescendo. By the last page of the chapter, the volume is nearly deafening, and it suddenly drops off to a whisper. This chapter brings out new complications in the debate the book has been engaged with, between illumination and painting, between absence and presence of the author, between seeing the world from above and looking toward the horizon, between tradition and innovation, between East and West -- none of these oppositions captures the meat of the debate but each is a facet. Here we hear the last words of the murderer and discover his identity -- and we hear the three master miniaturists composing an elegy for Master Osman's workshop and for the vanishing art of illumination. And there are moments where the narrative perspective shifts slightly and I can hear Pamuk speaking in his own voice about his writing. I feel like I am staring into the abyss. I am very much looking forward to reading the final chapter. Pamuk is a master of tragedy.

posted afternoon of September 16th, 2007: Respond

|  |

Saturday, September 15th, 2007

In his review at the Times Literary Supplement, Dick Davis describes chapter 51 of My Name is Red as "one of the most beguilingly lovely ten pages or so of art history I've ever read," which seems to me very well-put.

posted morning of September 15th, 2007: Respond

|  |

Friday, September 14th, 2007

They tell a story in Bukhara that dates back to the time of Abdullah Khan. This Uzbek Khan was a suspicious ruler, and though he didn't object to more than one artist's brush contributing to the same illustration, he was opposed to painters copying from one another's pages -- because this made it impossible to determine which of the artists brazenly copying from one another was to blame for an error. More importantly, after a time, instead of pushing themselves to seek out God's memories within the darkness, pilfering miniaturists would lazily seek out whatever they saw over the shoulder of the artist beside them. For this reason, the Uzbek Khan joyously welcomed two great masters, one from Shiraz in the South, the other from Samarkand in the East, who'd fled from war and cruel shahs to the shelter of this court; however, he forbade the two celebrated talents to look at each other's work, and separated them by giving them small workrooms on opposite ends of his palace, as far from each other as possible. Thus, for exactly thirty-seven years and four months, as if listening to a legend, these two great masters each listened to Abdullah Khan recount the magnificence of the other's never-to-be-seen work, how it differed from or was oddly similar to the other's. Meanwhile, they both lived dying of curiosity about each other's paintings. Later still sitting upon either edge of a large cushion, holding each other's books on their laps and looking at the pictures that they recognized from Abdullah Khan's fables, both the miniaturists were overcome with great disappointment because the illustrations they saw weren't nearly as great as those they'd anticipated from the stories they heard, but instead appeared, much like all the pictures they'd seen in recent years, rather ordinary, pale and hazy. The two great masters didn't then realize that the reason for this haziness was the blindness that had begun to descend upon them, nor did they realize it after both had gone completely blind, rather they attributed the haziness to having been duped by the Khan, and hence they died believing dreams were more beautiful than pictures. Chapter 51 seems to me like a huge achievement. It contains the climax of this book's inner story, the one about blindness and perfection, which I think is fully as mesmerizing and befuddling, as bestowing of clarity, as the outer story. I struggle to think of any other writer who can maintain this kind of structure in his tapestries -- Borges comes to mind but was not, after all, a novelist (in the contemporary sense of the word anyway -- and I'm not sure a sense of that word exists which would make it appropriate). Master Osman, who I believe has narrated once before but did not really grab me then, emerges as a powerful, tragic figure. (He is certainly the main character of this inner story.) This chapter marks the first time we are hearing about blindness, its seductive nature, its role in creation, from a character who has been identified throughout as nearing blindness. What could be more exquisite than looking at the world's most beautiful pictures while trying to recollect God's vision of the world?

posted evening of September 14th, 2007: Respond

| Previous posts about My Name is Red

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |