|

|

Sunday, November 15th, 2009

I'm a little over a quarter of the way through my rough draft translation of El viaje -- whether I end up revising it into something actually readable or no, it is a very useful exercise from the standpoint of helping me read the story -- it brings the imagery really sharply into focus, this process of reading the passage, sort-of understanding, setting out to render it in my own language, looking up unfamiliar terms, reading again... Goytisolo's punctuation of dialog (which seems to be shared pretty generally in the Spanish stories I've been reading) is to set quoted text off with em dashes -- I've been using this in the translation although it's possible that quotation marks would read more naturally. Not sure about that yet. Here is a passage of dialog I liked a lot, at the end of a drunken rant in which a circus impressario is assuring some of his performers (who have been stuck in this AndalusÃan town for several months without any money to pay for carriage) that he's got feelers out, he's going to get them passage to Lisbon, he's going to pay everybody...

The man took the bottle by its neck and guzzled another slug. His face was soaked in sweat and he was drumming his fingers on the top of his boot.

--People today, only interested in the vulgar --he said, looking at us--. The movies, every day at the movies... The work of an artist counts for nothing...

His tongue was giving him trouble with speaking and he looked around him, his gaze full of irritation.

--I had offers from Algeciras, from Tangiers, from Morocco, and I preferred to come here... They told me that in this town people appreciate art and now look... A sacrifice in vain... Like mixing margaritas for swine...

He was too drunk to go on and he hid his head between his hands. The waiter went and came back with the bottles and, passing by us, gave a wink.

--Don't pay him any attention... Every day it's like this.

Just then, the clock on the town hall struck nine.

It was time to go back; we got up.

The very brief paragraphs and heavy use of ellipses are characteristic of the story. I read a quote from Goytisolo somewhere that he considered Marks of Identity (1966, so half a decade after this) his "first real novel" -- maybe I should put that on my list.

posted evening of November 15th, 2009: Respond

➳ More posts about Juan Goytisolo

|  |

Saturday, November 14th, 2009

I'm glad I watched La Pointe-Courte when I did, as I'm now seeing loose parallels between it and everything I am reading... Sort of the archetypal melancholy romance.

Paco se habÃa sentado en cuclillas, algo más lejos y antes de abandonarme del todo, le pregunté:

--¿De qué vive la gente aqu�

Se entretenÃa en escurrir la arena entre sus dedos y no levantó, siquiera, la cabeza:

--De la pesca.

--¿Y tú? --Me extendà boca arriba y cerré los ojos--. ¿Qué quieres ser?

Su respuesta, esta vez, llegó en seguida:

--Mecánico.

Me dormÃ. TenÃa conciencia de que, al cabo de unas horas, olvidarÃa la fatiga del viaje y no deseaba otra cosa que cocerme lentamente, cara al sol.

En una o dos ocasiones, me desperté y vi que Dolores dormÃa también.

Con la vista perdida en el mar, Paco hacÃa escurrir aún la arena entre sus dedos.

Paco was squatting a bit further down the beach; before giving myself up to sleep, I asked him:

--What do people live on, here?

He was distractedly letting the sand run through his fingers; he didn't even raise his head:

--On fish.

--And you? --I turned my mouth up(?) and closed my eyes--. What do you want to be?

His response, this time, came directly:

--Mechanic.

I slept. I was aware that after a few hours, I'd forget the fatigue of the journey; I didn't want anything besides to let myself bake slowly, my face to the sun.

Once or twice, I woke up and saw that Dolores was sleeping too.

His gaze lost in the sea, Paco was still letting the sand run between his fingers.

I'm thinking I will work on a full translation of this story.

posted morning of November 14th, 2009: Respond

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

Friday, November 13th, 2009

A book of short stories by Juan Goytisolo, Para vivir aquà (1960, and containing the story La guardia that I was reading a couple of weeks ago), arrived in the mail this week, and I have been reading bits and pieces of it. The first two stories did not really grab me but as I look at the beginning of the third I am feeling pretty interested.

The journey

El cartel indicador se alzaba al final de la recta, con las letras pintadas de blanco, sobre el yugo y las flechas descoloradas. Desde la carretera se divisaba de nuevo el mar, liso y como bruñido por el sol y, más cerca, una zona cubierta de rastrojeras se extendÃa hasta los muros cuarteados de la fábrica en ruinas. A un extremo del campo, dos hombres batÃan la paja con sus bieldos. Era casi las doce y la calina que envolvÃa el paisaje, inventaba caprichosas espirales de celofán sobre el asfalto medio derretido.

Dolores frenó más allá del cartel y nos detuvimos a mirar, junto a la cuneta. El pueblo se extendÃa sobre una pendiente escalonada de terrazas y la cúpula de mosaico de la iglesia reverberaba a la luz del sol. De no ser por el bullicio y griterÃo de los chiquillos, se hubiera dicho que nadie vivÃa en él. Muchas casas estaban desmoronadas o en alberca, y sus fachadas maltrechas testimoniaban la existencia de una época de prosperidad y trabajo de la que la chimenea agrietada del teso y los restos alcinados de un molino constituÃan un recuerdo nostálgico. Ahora, toda la vida parecÃa concentrarse en el mar, y el puerto abrigaba medio centenar de embarcaciones protegidas por un espigón de obra, liso y curvado como una hoz.

-- ¿Qué te parece? --dije, señalando con el brazo, hacia el mar. --Como sitio tranquilo, lo es --repuso Dolores, sin gran entusiasmo.

Translation attempt below the fold.

The sign was up at the end of the block, with letters painted in white, over the cross-piece(?) and the faded arrow. From the road you could see the ocean again, flat and as if burnished by the sun and, closer in, a stubbled region stretched to the broken-down walls of a factory in ruins. At one end of the field two men were beating straw with their winnowing-forks. It was almost noon and the haze that shrouded the landscape was making up capricious spirals of cellophane above the half-melted asphalt.Dolores slowed down a bit by the sign and we turned to look, close by the ditch. The town extended across a spreading, terraced slope and the tile cúpola of the church reflected the sunlight. By not being a-bustle, full of children's cries, it let us know there was no one living in it. Many houses were dilapidated or fallen down(?), and their beaten-down façades were testament to there having been an epoch of prosperity and work, of which the cracked chimney at the top(?) and the remnants of a windmill constituted a nostalgic reminder. Now, all the life appeared concentrated in the sea, and the port sheltered half a hundred vessels, protected by a breakwater, smooth and curved like a sickle. --How does it look? --I said, gesturing with my arm toward the sea. --Like a peaceful spot, I guess --replied Dolores, without much enthusiasm.

↻...done

posted evening of November 13th, 2009: Respond

|  |

Sunday, November 8th, 2009

Buscaba inútilmente la forma de soportar el dolor, daba vueltas por la casa, me daba un baño muy caliente, me acostaba, me volvÃa a levantar, daba un paseo, me dejaba caer sobre el sofá, de nuevo fatigada...

Soledad Puértolas, "Masajes"

I'm not at all sure how to translate much of this story -- it is only the second thing I have read in Spanish without a translation available to help me flesh out what the meanings of the words and constructions were. I'm understanding it only in a pretty rough, impressionistic way, the images are quite out of focus. This makes the impact of the words as words stronger in a way, the sound of the language a larger proportion of the experience: and I'm really struck by the shift in tense here between me acostaba and me volvía a levantar -- "I was walking around the house, drawing myself a very hot bath, was putting myself to bed, I got up again, I was going for a walk, letting myself fall on the sofa, suddenly fatigued..." Many of the constructions in this story seem strange to me and hard to make sense of -- this is contributing certainly to the fuzziness of my reading experience.

Me inquietó y acabó, sobre todo, molestándome, porque me hacÃa estar pendiente de la hora y del silencio de la casa y imaginar, antes de escucharse, el ruido del timbre abriéndose camino hacia mÃ.

It's just really hard for me to match up subjects and objects and tenses in this sentence -- I get that she's saying she was troubled by the phone call (which was mentioned in the last paragraph and is definitely the subject of Me inquietó) -- "It disturbed me and had just, most of all, been bothering me, because (?) it made me be hanging from the hour and from the silence of the room and to imagine, before hearing it, the noise of the ringer making its way towards me." (Or something like that.) El ruido del timbre abriéndose camino hacia mí is a particularly nice image, provided I am reading it correctly. I'm sort of happy to find an author that I like but am not heavily invested in to practice this kind of language comprehension on... I am also thinking Goytisolo will fit the bill in this way.

Another example (the narrator is speaking of a health club employee who had in the previous paragraph shown her around the facility) --

Su amiabilidad, su interés por mÃ, tenÃan una nota atificial, falsa, como si alguien la hubiera convencido de que tenÃa que ser asÃ. O sencillamente era asà como quien es hosco y antipático desde la cuña o como quien tiene una especial habilidad para los idiomas o para las installaciones eléctricas.

"Her friendliness, her interest in me, bore a note of artificiality, falsehood, as if someone had convinced her she needed to act like that. Or simply like when somebody is hostile and antisocial from the cradle, or somebody has a particular ability for languages or for electrical work." -- None of the entities separated here by or's seem to me like they can sustain that kind of relationship with one another.

↻...done

posted evening of November 8th, 2009: 1 response

➳ More posts about Soledad Puértolas

|  |

Saturday, October 10th, 2009

What a way to be introduced to a character! From Juan Goytisolo's La guardia:

Recuerdo muy bien la primera vez que lo vi. Estaba sentado en medio del patio, el torso desnudo y las palmas apoyadad en el suelo y reÃa silenciosamente. Al principio, creà que bostezaba o sufrÃa un tic o del mal de San Vito pero, al llevarme la mano a la frente y remusgar la vista, descubrà que tenÃa los ojos cerrados y reÃa con embeleso. ...

El muchacho se habÃa sentado encima de un hormiguero: las hormigas le subÃan por el pecho; las costillas, los brazos, la espalda; algunas se aventuraban entre las vedijas del pelo, paseaban por su cara, se metÃan en sus orejas. Su cuerpo bullÃa de puntos negros y permanecÃa silencioso, con los párpados bajos.

I remember well the first time I saw him. He was sitting in the middle of the courtyard, his torso naked and his palms resting on the ground, laughing silently. At first, I thought he was yawning or he suffered from a tic or from St. Vitus' Dance; when I raised my hand to my forehead and cleared my view, I found he had his eyes closed and was laughing, in a trance. ...

The kid had sat himself down on top of an anthill: ants were crawling across his chest; his ribs, his arms, his back, some were venturing among his tangled hair, passing over his face, entering into his ears. His body swarmed with dots of black and he remained silent, his eyelids down.

Wow. This is a real trip to visualize -- I've been looking forward to reading this story of Goytisolo's, which is the last one in the book of Spanish-language stories I've ben reading for the past few weeks, especially since Badger recommended him to me as a major influence on Pamuk... I'm not understanding this story well enough yet to talk about it in the context of literary influence or parallels... but man! What a stunning image.

Update: added a little context from the first paragraph.

posted afternoon of October 10th, 2009: 1 response

➳ More posts about Cuentos Españoles/Spanish Stories

|  |

Sunday, October 4th, 2009

He notado que esas personas hablan con la mayor liviandad, sin tener en cuenta que hablar es también ser.I've noticed that these people [European colonists] speak with the greatest frivolity, without taking into account that to speak is also to be.

This line (from Walimai by Isabel Allende) is resonating, sticking in my mind as something deserving of further consideration. Not sure yet what to make of it...

posted evening of October 4th, 2009: Respond

|  |

|

I've been poking around in Cuentos Españoles this weekend -- I got another similar book yesterday, Cuentos en Español (Penguin, 1999)* and the story that really caught my attention was La indiferencia de Eva, by Soledad Puértolas. The pace and rhythm of the story are almost perfect and I'm finding it easy to identify with her characters, to place myself in her scenes. I would like recommendations for further reading of her work, if any of you have read it -- she has several novels and collections of short stories, though I am finding nothing in translation.**

* and apparently Penguin also published bilingual collections of Spanish stories in 1966 and 1972 -- I'm surprised at how much of this I am finding! ** This is wrong -- the novel Bordeaux has been translated; and at least Google Books thinks that one of her stories appears in the collection After Henry James, though I haven't been able to find any reference to this collection elsewhere.

posted evening of October 4th, 2009: 2 responses

|  |

Sunday, September 27th, 2009

-- Y para guardar un secreto que lo era a voces, para ocultar un enigma que no lo era para nadie, para cubrir unas apariencias falsas ¿hemos vivido asÃ, Tristán? ¡Miseria y nada más! Abrid esos balcones, que entre la luz, toda la luz y el polvo de la calle y las moscas, mañana mismo se quitará el escudo.-- And so to guard a secret which was no secret, to shroud a mystery which was clear to everyone, to conceal our false appearances we have lived like this, Tristán? -- Misery, nothing more! Open these balonies, let the light in, all the light and the dust of the street and the flies, and tomorrow we will take down the coat of arms.

I was so wrapped up in the story of The Marqués of LumbrÃa yesterday evening, I was actively cheering Carolina on as she said this -- then I took a step back from the story and asked myself, am I judging Unamuno differently because he is "foreign"? If a present-day Pierre Menard were writing these lines I might think the plot was corny and over-determined. A couple of things that ran through my head --

- Unamuno is "foreign" -- he is of Spain, he is of the 19th Century, he is of Catholicism. I am exoticising the story by attributing these things to it, which are all outside my experience. This seems like a not-great way of reading, like something that would prevent me from really understanding the story. ...There may be some truth to this but I would be leery of giving it too much weight.

- I am a less sophisticated reader in Spanish than in English. The barrier separating me from the text, the time it takes to figure out what is being said, is making my reaction to the story more immediate, and delaying my critical/analyical reaction... I'm not sure that this is a coherent idea -- it is sort of tantalizing, to think that I can get into a younger, more naïve head by reading foreign language.

But in the end I think what is making the plotting of this story work, where I might find the same plot elements cornball in another context, is Unamuno's imagery, his descriptive voice. The reading of the story has felt up until this point like looking at dark paintings, there was a sense of claustrophobia imagining the characters as figures on dimly-lit canvasses -- so much so that when Carolina speaks out and orders the windows and balconies uncovered, I get the sense of her figure tearing itself away from the canvas -- this is an interesting image regardless of how much verisimilitude I'm prepared to accord the plot elements.

posted morning of September 27th, 2009: Respond

➳ More posts about Miguel de Unamuno

|  |

Friday, September 25th, 2009

I hope a movie has been made of Unamuno's El marqués de LumbrÃa; this opening paragraph would be spectacular on the screen: La casona solariega de los marqueses de LumbrÃa, el palacio, que es como se le llama en la adusta ciudad de Lorenza, parecÃa un arca de silenciosos recuerdos del misterio. A pesar de hallarse habitada, casi siempre permanecÃa con las ventanas y los balcones que daban al mundo cerrados. Su fachada, en la que destacaba el gran escudo de armas del linaje de LumbrÃa, daba al MediodÃa, a la gran plaza de la Catedral, y frente a la ponderosa fábrica de ésta, pero como el sol bañaba casi todo el dÃa, y en Lorenza apenas hay dÃas nublados, todos sus huecos permanecÃan cerrados. Y ello porque el exelentÃsimo señor marqués de LumbrÃa, Don Rodrigo Suárez de Tejada, tenÃa horror a la luz del sol y al aire libre. "El polvo de la calle y la luz del sol-solÃa decir-no hacen más que deslustrar los muebles y hechar a perder las habitaciones, y luego, las moscas..." El marqués tenÃa verdadero horror a las moscas, que podÃan venir de un andrajoso mendigo, acaso de un tiñoso. El marqués temblaba ante posibles contagios de enfermedades plebeyas. Eran tan sucios los de Lorenza y su comarca...

The ancestral mansion of the Marquéses of LumbrÃa, the palace as it was called in the gloomy city of Lorenza, appeared as a chest of silent memories of the mysterious. In spite of its being in fact occupied, the windows and balconies which gave out onto the world were almost always closed. The façade, where the great coat of arms of the LumbrÃan lineage stood forth, looked south*, onto the great square of the Cathedral, whose ponderous construction it faced, but as the sun was shining all day long, and in Lorenza there are hardly any cloudy days, all of its openings remained closed. And this was because the excellent Señor Marqués of LumbrÃa, don Rodrigo Suáres de Tejada, abhorred the light of the sun and fresh air. "The dust of the street and the light of the sun -- he used to say -- do no more than dull the furniture's shine and spoil the rooms; not to mention the flies..." The Marqués was deathly afraid of flies, which might have come from a ragged, miserable beggar. The Marqués trembled at the thought of catching plebian diseases. And they were so filthy, the Lorenzans and the countryfolk...

...But it looks like no; several of his stories and books have been filmed but not this. *How great a dialect for "south" is "noon"? A lovely one.

posted evening of September 25th, 2009: Respond

➳ More posts about The Movies

|  |

Sunday, September 20th, 2009

Next story in Cuentos Españoles after La fuerza de la sangre (skipping over several centuries -- did nothing happen in Spain between the early 1600's and the late 1800's?) is El libro talonario by Pedro Antonio de Alarcón. A good solid story, a narrative voice I can relate to. And I find that a couple of years ago, it was made into a short movie! The movie is well done -- it gets across the idea of the story without adhering slavishly to its plot, and brings a modern perspective to it. Take a look, it's a pleasant 20 minutes:

posted evening of September 20th, 2009: Respond

| Previous posts about Short Stories

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

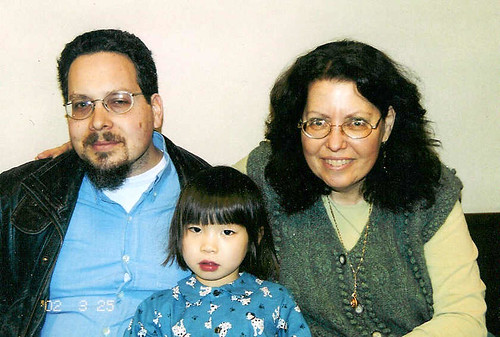

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |