|

|

Friday, March 13th, 2009

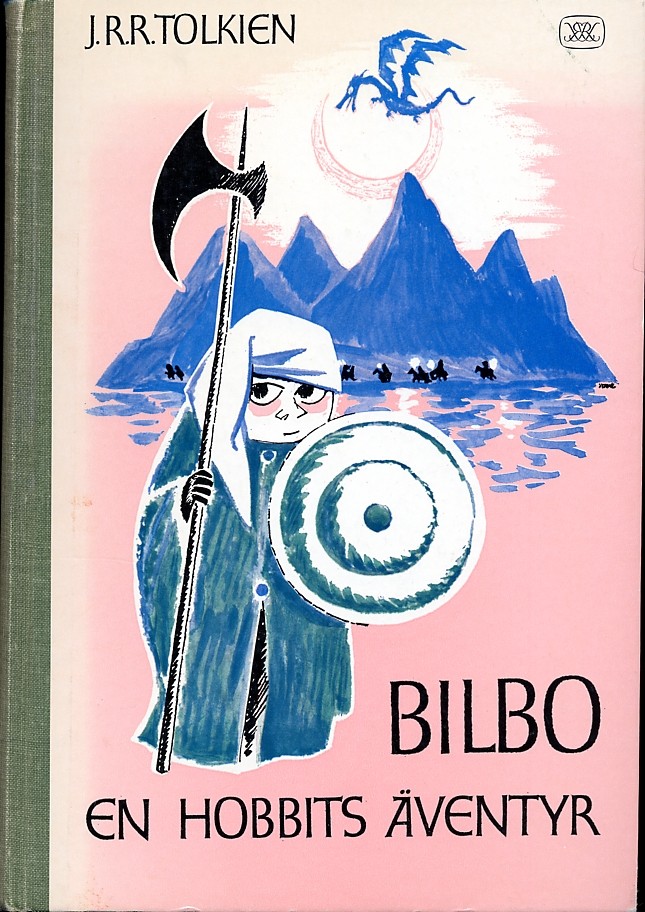

My memory of reading The Hobbit (which happened about 30 years ago) has always been a very positive one, of being into the book in a pre-analytical way and just loving it, and I was always scared to pick it up to reread for fear that quality of the experience would be gone. I am happy to report (a few chapters in) that the quality is not only present but is augmented by seeing the page with a little more experienced (hopefully wiser but certainly more familiar with the world) eye. My memory of reading The Hobbit (which happened about 30 years ago) has always been a very positive one, of being into the book in a pre-analytical way and just loving it, and I was always scared to pick it up to reread for fear that quality of the experience would be gone. I am happy to report (a few chapters in) that the quality is not only present but is augmented by seeing the page with a little more experienced (hopefully wiser but certainly more familiar with the world) eye.

Don't miss Tove Jansson's illustrations for a Swedish edition of The Hobbit. (And it just occurs to me, oh yeah! Hobbits and Moomins have certain distinct similarities! Also Hobbits and Hemulens.)

posted evening of March 13th, 2009: Respond

➳ More posts about The Hobbit

|  |

Sunday, March 8th, 2009

Saramago posts today about International Women's Day:

I've just been watching the TV news, demonstrations by women all over the world, and I'm asking myself one more time what disgraceful  world this is, where half the population still has to take to the streets to demand what should be obvious to everyone... world this is, where half the population still has to take to the streets to demand what should be obvious to everyone...

They say that my greatest characters are women, and I believe this is correct. At times I think the women whom I've described are suggestions which I myself would like to follow. Perhaps they are just models, perhaps they do not exist, but one thing I am sure of: with them, chaos could never have established itself in this world, because they have always known the scale of the human being.

I'm not completely sure about the translation in that last paragraph; it sounds pretty stilted the way I have written it. Possibly this is true of the original as well -- "chaos could never have established itself in this world" strikes me as a very strange thing to say, when the world is fundamentally chaotic -- and I don't see Saramago's women as imposers of order on natural chaos. This may be a clue into Saramago's understanding of the universe; I could see a reading of The Stone Raft in which the world is understood as an inherently ordered structure, and the characters (male and female, but particularly Joana) are keyed in to this natural order in opposition to humanity's chaos. Alternately I could be mistranslating, always a possibility.

posted evening of March 8th, 2009: Respond

➳ More posts about Saramago's Notebook

|  |

Friday, March 6th, 2009

I got in touch with the friend to whom I loaned Blindness; she sent me the authorized translation of the epigraph I've been wondering about for the past few days. I got in touch with the friend to whom I loaned Blindness; she sent me the authorized translation of the epigraph I've been wondering about for the past few days.

If you can see, look.

If you can look, observe. This is just right -- "If you can see" makes much better sense as an opening phrase than "If you can look"; and then on the second line, "If you can look" reads alright because you already have the structure set up to understand it in.

Saramago attributes this line to the "Book of Exhortations", which if I'm understanding right is Deuteronomy. It would be interesting to find out where it is in that book and see how e.g. the King James translation renders it. ...Looking further, it seems like "Book of Exhortations" is a pretty generic term -- it can refer to a lot of different prophetic writings. I wonder what Saramago's source for this line is. Update: Further investigation of the source here.

posted morning of March 6th, 2009: 2 responses

➳ More posts about Blindness

|  |

Thursday, March 5th, 2009

Saramago takes another look at the epigraph, and makes me understand that I had been misreading it in a key way:

In a conversation yesterday with Luis Vázquez, closest of friends and healer of my ailments, we're talking about the film by Fernando Meirelles, just premiered in Madrid, even though we could not be in attendance, Pilar and I, as we intended to be, for a sudden bout of chills obligated me to retire to my chamber, or confined me to bed, in the elegant phrasing in use not so long ago. The conversation soon turned to the public's reactions during the exhibition and afterwards, highly positive according to Luis and to other trustworthy witnesses... We moved from there, naturally, to talking about the book and Luis asked me if we could look over the epigraph which opens it ("Si puedes mirar, ve, si puedes ver, repara"), for in his opinion, the action of seeing [ver] encompasses the action of looking [mirar], and therefore, the reference to looking could be omitted without bias to the meaning of the phrase. I could not come up with a reason to give him, but I thought that I should have other reasons to consider, for example, the fact that the process of vision occurs three stages, successive but in some manner autonomous, which can be stepped through as follows: one can look and not see, one can see and not observe, according to the degree of attention which we pay to each of these actions. We know the reaction of a person who, having just checked his wristwatch, returns to check it when, at that moment, somebody asks him the time. That was when light flooded into my head concerning the origin of the famous epigraph. When I was small, the word "observe", always supposing I already knew it, was not for me an object of primary importance until one day an uncle of mine (I believe that it is Francisco Dinis of whom I am speaking in this brief memoir) called my attention to a certain way of looking that bulls have, which almost always, he then demonstrated, is accompanied by a certain way of raising the head. My uncle said: "He has looked at you, when he looked at you, he saw you, and now it is different, he is something else, he is observing." This is what I told Luis, which immediately won the argument for me, not so much, I suppose, because it convinced him, but because the memory made him remember a similar situation. A bull looked at him as well, and again this movement of the head, again this looking which was not simply seeing, but observation. We were at last in agreement.

So, reparar is not "fix" as I had been thinking, but "observe" or "contemplate". The dictionary entry confirms that the word can be used in this sense. I'm still (like Luis) a bit dissatisfied with the relationship between mirar and ver in the first part of the epigraph.

posted evening of March 5th, 2009: 1 response

➳ More posts about José Saramago

|  |

Tuesday, March third, 2009

Saramago is looking back on writing the epigraph for Blindness: Si puedes mirar, ve.

Si puedes ver, repara.

I wrote this for Blindness, already a good couple of years ago. Now, when the film based on this novel is making its debut in Spain, I've encountered the phrase printed on the bags of the 8½ bookstore and on the inside front cover of Fernando Meirelles' making-of book, which this same bookstore's publishing arm has edited with skill. At times I have said that by reading the epigraph of any of my novels, one will already know the whole thing. Today, I don't know why, seeing this, I too felt a sudden impulse, felt the urgency of repairing, of fighting against the blindness. [links are my additions -- J]

I'm curious about how to translate that epigraph. (And surprised that I don't remember this epigraph from when I read Blindness, and annoyed that I cannot go check how Pontiero translated it, because I lent it to a friend...) The sense of it is, "If you can see, see. If you can see, repair." -- Obviously this does not sound good in English because the distinction between mirar and ver is missing, and the transitive structure is lost. The literal translation of the first sentence would be "If you can look, see" -- but I'm guessing the sense of Si puedes mirar is something more like "if you are able to see", i.e. if you are not blind. It seems like ve has a more transitive sense, "see something, some injustice" (although the object is omitted, as it is with repara) -- where mirar is intransitive.

(There is an important misreading in this post, as regards the verb reparar -- see later post for the correction.)

posted evening of March third, 2009: 4 responses

➳ More posts about Translation

|  |

Sunday, March first, 2009

Saramago recommends as "one of the most skilled and original" of Portugal's new generation of novelists, Gonçalo M. Tavares. Doesn't look like Sr. Tavares has any works published in English yet (this might be wrong -- his translations page lists rights for most of his works having already been bought for "English in India only" -- but it's not clear that those translations have been published) but definitely someone to keep an eye out for. When he received the Saramago Prize in 2005, Saramago said "Jerusalém is a great book, and truly deserves a place among the great works of Western literature. Gonçalo M. Tavares has no right to be writing so well at the age of 35. One feels like punching him!"

posted evening of March first, 2009: 5 responses

|  |

Saturday, February 28th, 2009

Borges categorizes 5 of Poe's stories as detective stories, I just wanted to list them with links to sources: If I'm reading him correctly, he thinks that detective stories are spoiled if you know the solution going in*, and that Poe's stories have been spoilt because we all know how they're going to turn out. But this solution [the end of "Murders in the Rue Morgue"] is not a solution for us, because we all know the outcome prior to reading Poe. This, of course, takes away much of its power....

Not sure how to react to this -- I think I remember being surprised by the ending of "Murders in the Rue Morgue", which I read as a child; but it was so many years ago, I could be wrong. Borges goes ahead in the next sentence and spoils the ending for any of his listeners who do not already know it, which seems a little mean-spirited.

* This is a little curious taken side-by-side with his assertion in "The Book", that re-reading is more important than reading -- it seems like an inescapable conclusion from these two statements, that detective fiction is not important literature...

posted afternoon of February 28th, 2009: Respond

➳ More posts about Borges oral

|  |

|

I'm trying to understand what Borges thought of Poe -- there are different, and conflicting, levels of his opinion to take into account. As I said yesterday, he is pretty dismissive of the poems and stories themselves -- he spends a few pages addressing Poe's detective stories one by one, and none of them comes off very well. But he still believes Poe to be a genius, and one of the most important authors influencing modern literature.

I have said, Poe was the creator of an intellectual temperament in literature. What happened after Poe's death? He died, I believe in 1849. Whitman, his other great contemporary, penned an obituary* of him, saying that Poe was a performer who only knew how to play the low notes of the piano, who did not represent American democracy -- a claim which Poe had never made for himself. Whitman did him an injustice, and so did Emerson.There are critics, today, who underestimate him. But I believe that Poe, if we take his works in aggregate, has the œuvre of a genius, even if his stories (excepting the narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym) are defective. Nonetheless, taken together they construct a character, a character more vividly present than the characters he created, more vividly present than Charles Auguste Dupin, than the crimes, than the mysteries which fail to scare us.

This seems to be his final judgement of Poe -- the rest of the lecture he spends discussing the flourishing of the detective story in Britain and its abasement in the US. So he gives Poe credit for inventing a genre, for inventing a style of reading, for inventing Borges himself -- at one point he says "we ourselves" read differently by virtue of having Poe's invention as part of our heritage. I guess he believes Poe to be a literary genius but not a great author.

* I haven't been able to find the source for this obituary on the web. Update -- found it!

posted afternoon of February 28th, 2009: 3 responses

➳ More posts about Jorge Luis Borges

|  |

Friday, February 27th, 2009

As I read this lecture I'm beginning to think that Borges does not really think that much of Poe as a writer -- interesting because he says (as I noted below) that Poe changed the course of the history of literature, that Poe invented a genre and a manner of reading hugely important in our time. Of Poe as a poet, Borges says we have "a much lesser Tennyson"; he quotes Emerson in calling Poe a "jingleman." There is a hugely entertaining two-page digression in which Borges imagines the process of writing "The Raven," which is by itself worth the price of admission. Of his prose, Borges says he is "more extraordinary in the aggregate of his work, in our memory of his work, than in any of the pages of his work."

Update: I found what might be the original reference for Emerson calling Poe "the jingle man" -- the May 20, 1894 edition of the NY Times, under the headline "Emerson's Estimate of Poe" (only available as PDF) quotes the April 1894 Blackwood's Magazine: "Whom do you mean?" asked Emerson with an astonished stare, and on the name being repeated with extreme distinctness, "Ah, the jingle man!" returned Emerson, with a contemptuous reference to the "refrains" in Poe's sad lyrics.

Update II: Fixed a blunder in my translation -- I had omitted a phrase ("in the aggregate of his work") that changes the sense of the quotation.

posted evening of February 27th, 2009: 2 responses

➳ More posts about Edgar Allen Poe

|  |

Thursday, February 26th, 2009

Borges starts out by talking about how one reads detective stories.

To think is to generalize; we need the useful archetypes of Plato to be able to make any claim. So: why shouldn't we affirm that there are literary genres? I will add a personal observation: literary genres depend, perhaps, less on the texts themselves than on the manner in which they are read. The æsthetic fact requires a conjunction of reader and text; only then does it exist. It is absurd to suppose that a volume is anything more than a volume. It starts to exist when the reader opens the volume. Then the æsthetic phenomenon comes into existence, which could be imagined from the moment when the book was engendered.

And there is an actual type of reader, the reader of detective fiction. This reader -- this reader whom we encounter in every country of the world and who numbers in the millions -- was brought into being by Edgar Allen Poe. Let us suppose that this reader did not exist -- or let's suppose something perhaps more interesting, that we are dealing with a person far removed from ourselves. He could be a Persian, a Malay, a hayseed, a kid -- some person whom we tell that the Quixote is a detective novel; let us suppose that this hypothetical person has read detective novels, and he begins reading the Quixote. So how is he going to read it?

Somewhere in la Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember, not long ago there lived a gentleman... and already this reader is filled with suspicions, for the reader of detective novels is a skeptical reader, suspicious, particularly suspicious.

For example, when he reads: Somewhere in la Mancha..., of course he supposes that this did not take place in la Mancha. Then: ...whose name I do not care to remember..., -- why does Cervantes not care to remember? Without a doubt because Cervantes is the murder[er], is at fault. Then, ...not long ago...; it may be that what has already happened is not as terrifying as the future.

The first two paragraphs of this passage seem just fantastic to me (given that I didn't think there was any real need in the first place, to defend the legitimacy of talking about genre) -- the idea that literary genre is determined by an interaction between the reader and the text has a whole lot of room for interesting stuff to com out of it. The idea that Edgar Allen Poe created the reader of detective stories is a nice little nugget of thought. And the thought experiment of reading Don Quixote as a detective story is a great idea, of course bringing to mind Borges' story about Pierre Menard. But when he embarks on the experiment, he goes off on the wrong track. The suspicions that Borges attributes to the reader of detective fiction are suspicions about the intent of the narrator, of the author of the Quixote. But the unreliable narrator does not belong to the detective story, and suspicion of him does not belong to the detective story reader; Laurence Sterne predates Poe by a hundred years, and he did not invent the unreliable narrator. (If memory serves, for that matter, the narrator of the actual Quixote is himself not particularly reliable.*) It's been a while since I read any genre detective stories, but the way I recall reading them is being suspicious of the characters and the ways they presented themselves; the narrator (speaking here of stories in the third person or narrated by the detective, and not considering the Raymond Chandler branch of the genre) did not lie, though he might fail to disclose valuable information or might himself be deceived.

So, there's my quibble with this lecture -- which I have not read in full yet. This reading a language I do not understand seems to really point me in the direction of reading closely, at least...

...Looking ahead, some really great stuff in the body of this lecture. Stay tuned, I'll try and write more this evening. Borges thinks the two authors "without whom literature would not be what it is today" are Poe and Whitman.

* I mean to say, it seems completely natural to wonder why Cervantes does not care to remember the place where his novel begins -- but it's not because I suspect Cervantes of being the guilty party, and I don't believe it's because I have read detective stories. I wonder if a 17th-Century reader would have this reaction -- it's hard for me to imagine any other way of reacting to that sentence.

posted evening of February 26th, 2009: 11 responses

➳ More posts about Don Quixote

| Previous posts about Readings

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |

Sydney on Guestbook